Christie Huck

When Parents Take Charge

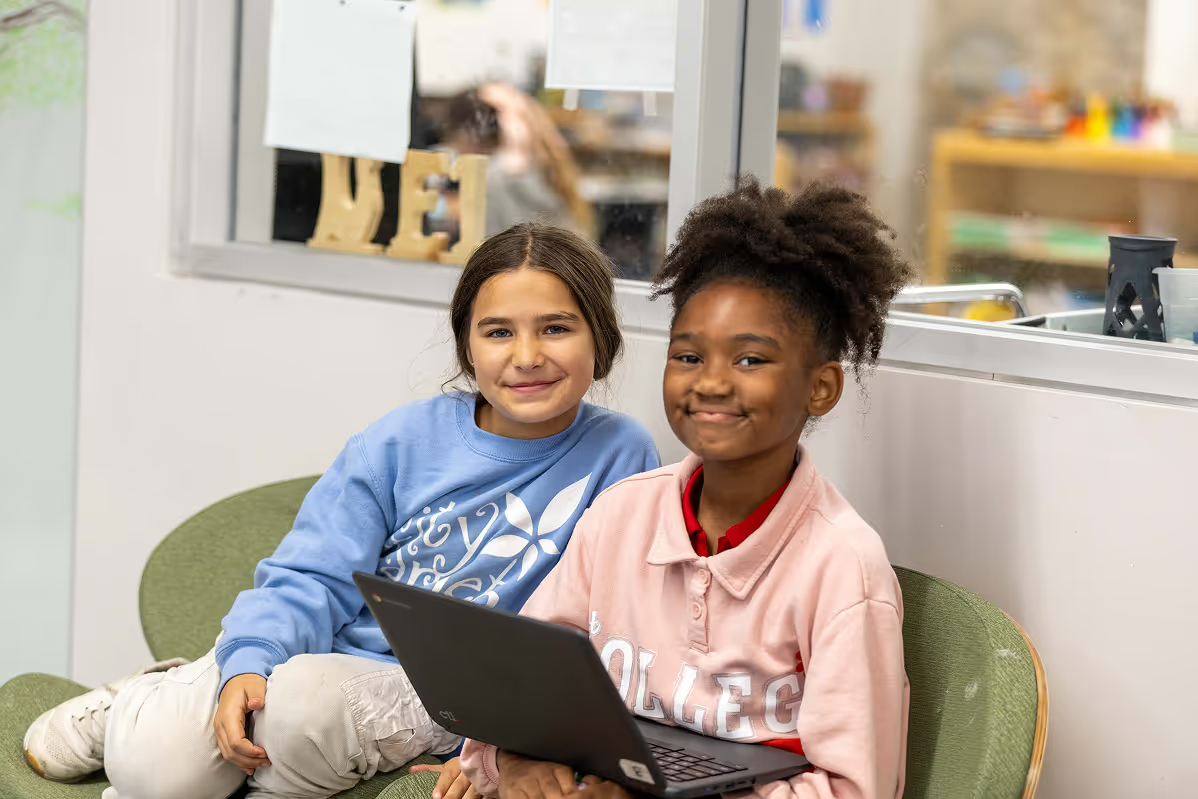

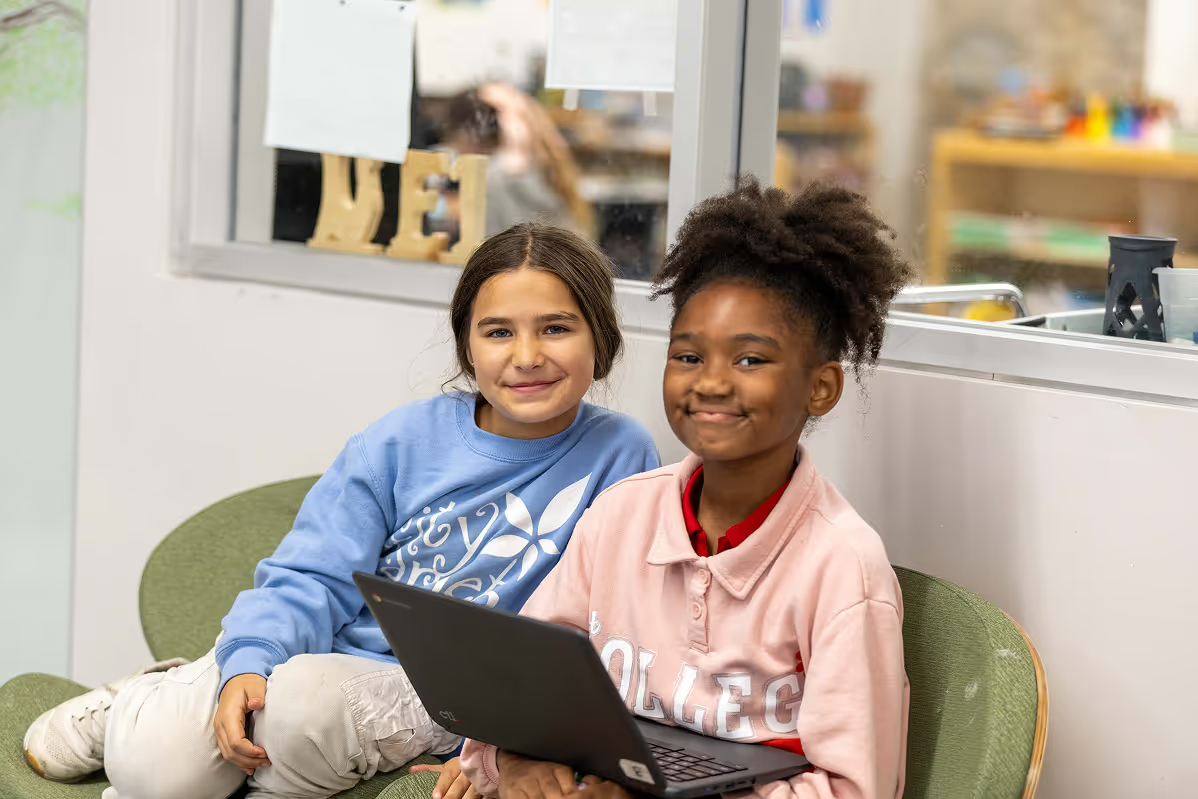

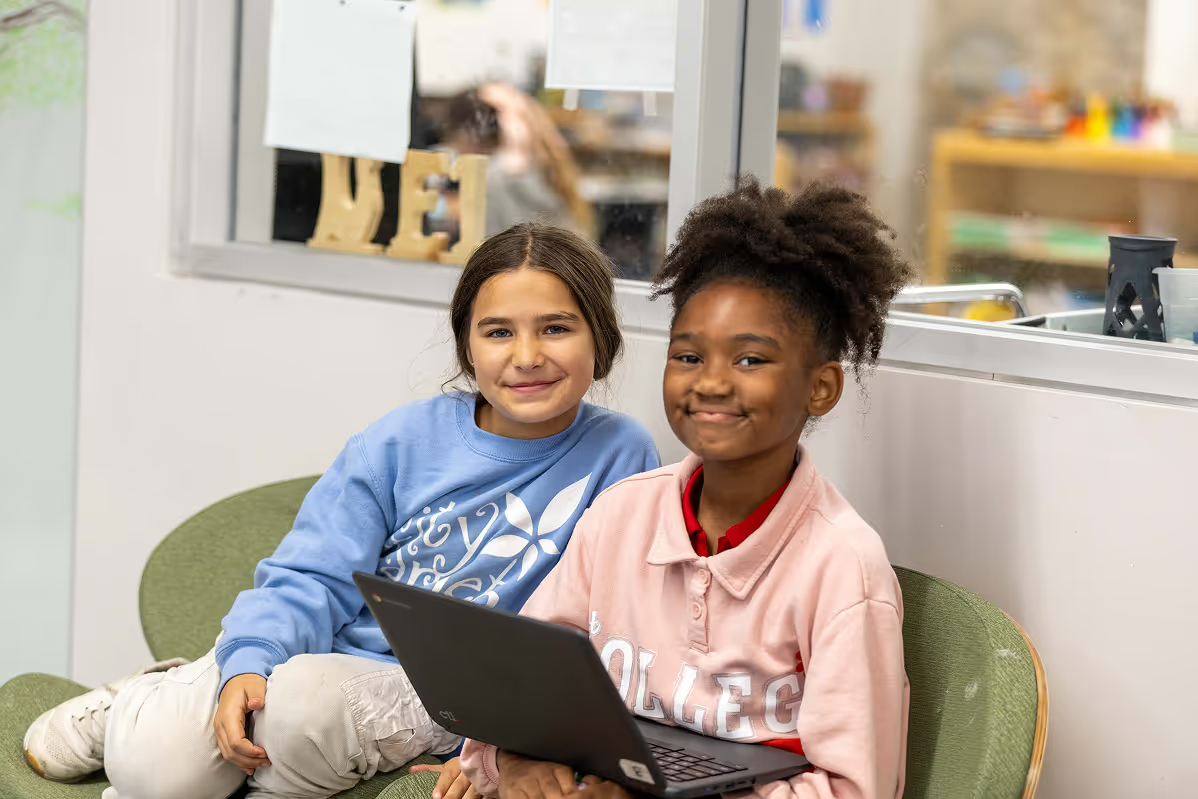

Founded by parents 20 years ago, City Garden Montessori has become a public charter model for how community voices and vision can shape public education

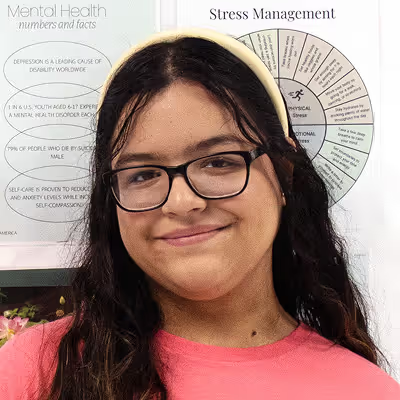

It was Leap Day 2004 when Christie Huck first brought her son to visit City Garden Montessori, a low-cost private preschool in St. Louis. The teacher measured each child’s height with a length of ribbon that would be cut and saved until the next Leap Year, four years later. “It sparked a discussion about time, how much they grew in the past year, and imagining four years from now,” Huck recalls. “I was just enthralled by the conversation these preschoolers were having.”

She enrolled her son at City Garden and quickly fell in love with the school’s individualized, child-centered approach. A community activist with a background in social justice, Huck had moved to the diverse Shaw neighborhood because it was one of the few racially and economically diverse communities in St. Louis. However, when she began looking for academically rigorous and racially integrated elementary school options, she was frustrated by the lack of choices.

Huck and Reine Bayoc, another parent at City Garden, approached Trish Curtis, one of the school’s founders, to see if she might consider expanding into the elementary grades. Curtis floated the idea of creating a tuition-free, community-based public charter school. “Our greatest advantage was not knowing what we didn’t know,” Huck says. “If we had had a full picture of it all, I’m not sure we would have done it.”

“Our greatest advantage was not knowing what we didn’t know.”

In 2006, there were few community-driven public charter schools in St. Louis. Huck and Bayoc set out to drum up interest from other City Garden parents and in the surrounding neighborhood. Huck carried informational flyers in her back pocket and handed them out to parents while at the playground with her kids or at the public library. “This was before social media,” she says, chuckling. “Sometimes I’d be out taking a walk and just casually start chatting about schools. It was very grassroots.”

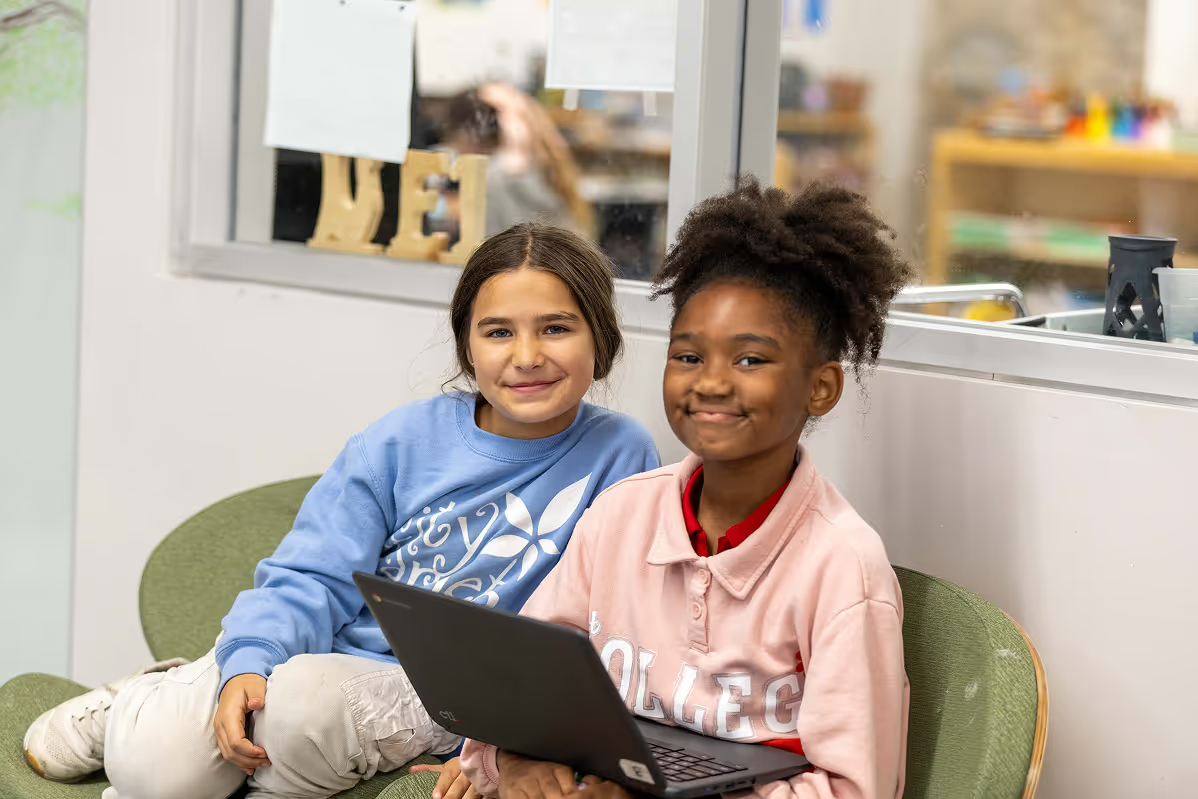

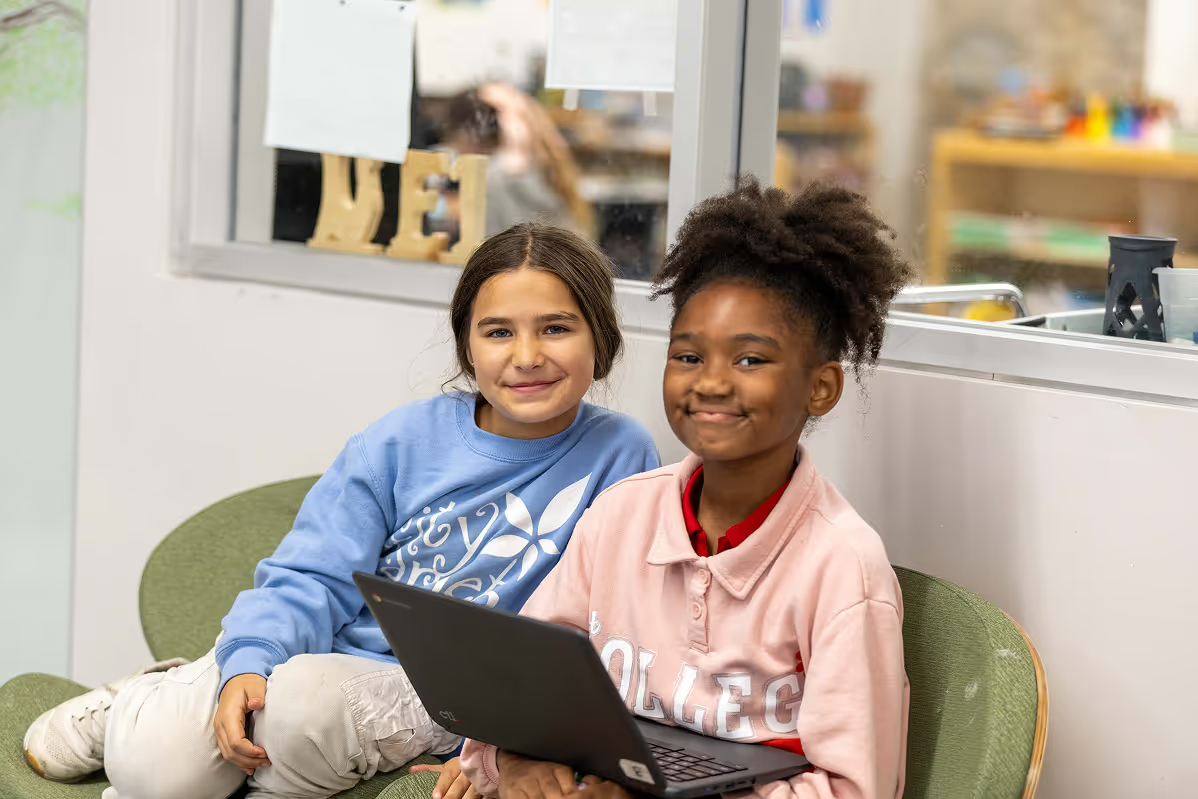

Eventually, eight families joined the effort and formed a planning committee. Over the course of the next two years, Huck and Bayoc hosted meetings in their living rooms and at parks around the city, and the group crafted a vision for a community-run, neighborhood Montessori school that would serve a racially and socioeconomically diverse student body.

In the fall of 2008, City Garden opened as a K-3 school with a class of 53 students in the basement of a local church. Huck joined staff part-time to help get the school up and running, but after a series of leaders exited the top post, the board asked her to step into the role.

Now in her fifteenth year as City Garden’s executive director, Huck describes that early learning curve as a baptism by fire. With no experience or training in leading a school, she immersed herself in researching legal matters, school finance, and public charter compliance and leaned heavily on the advice of other public charter school leaders. When things got tough, Huck says the promise of the school parents had envisioned for their kids pushed them forward.

“It’s an example of what’s possible when a group of parents and teachers and community members really want something to happen,” Huck says. “The structure of public charter schools allowed people like me and Reine and Trish to dig in and figure out what it was going to take and then build it.”

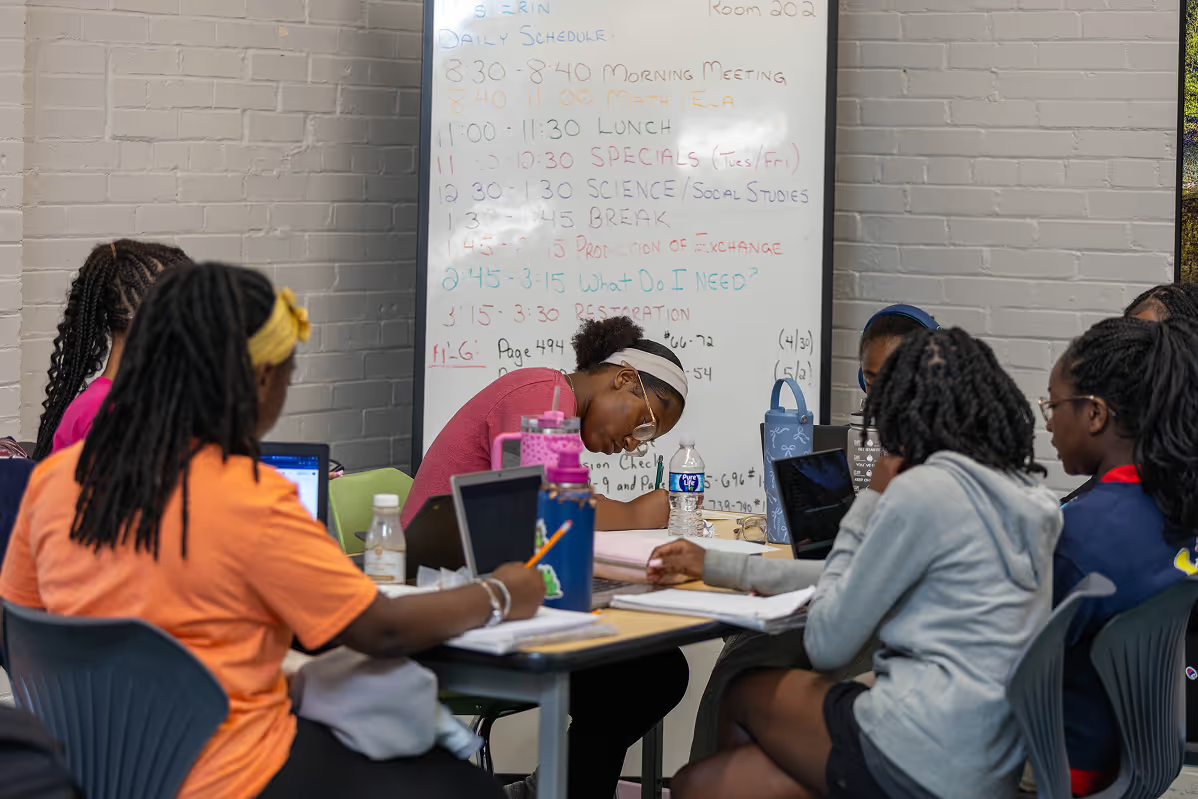

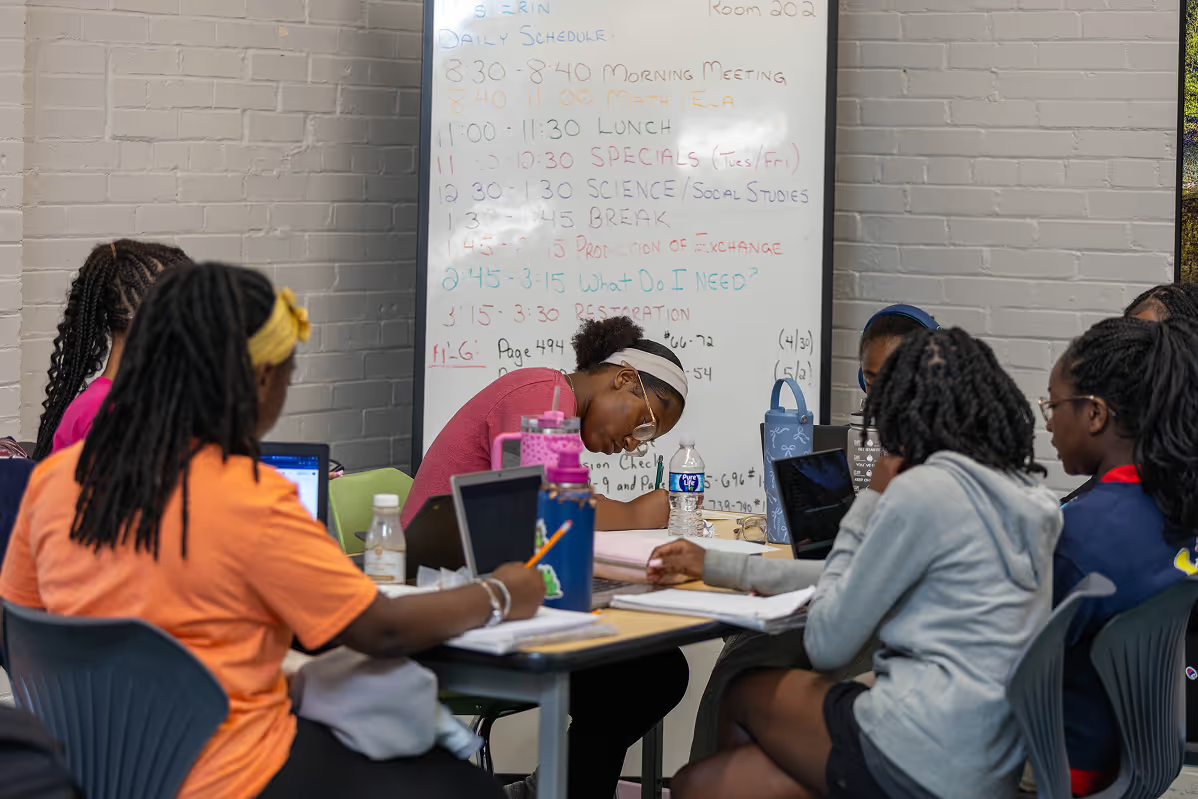

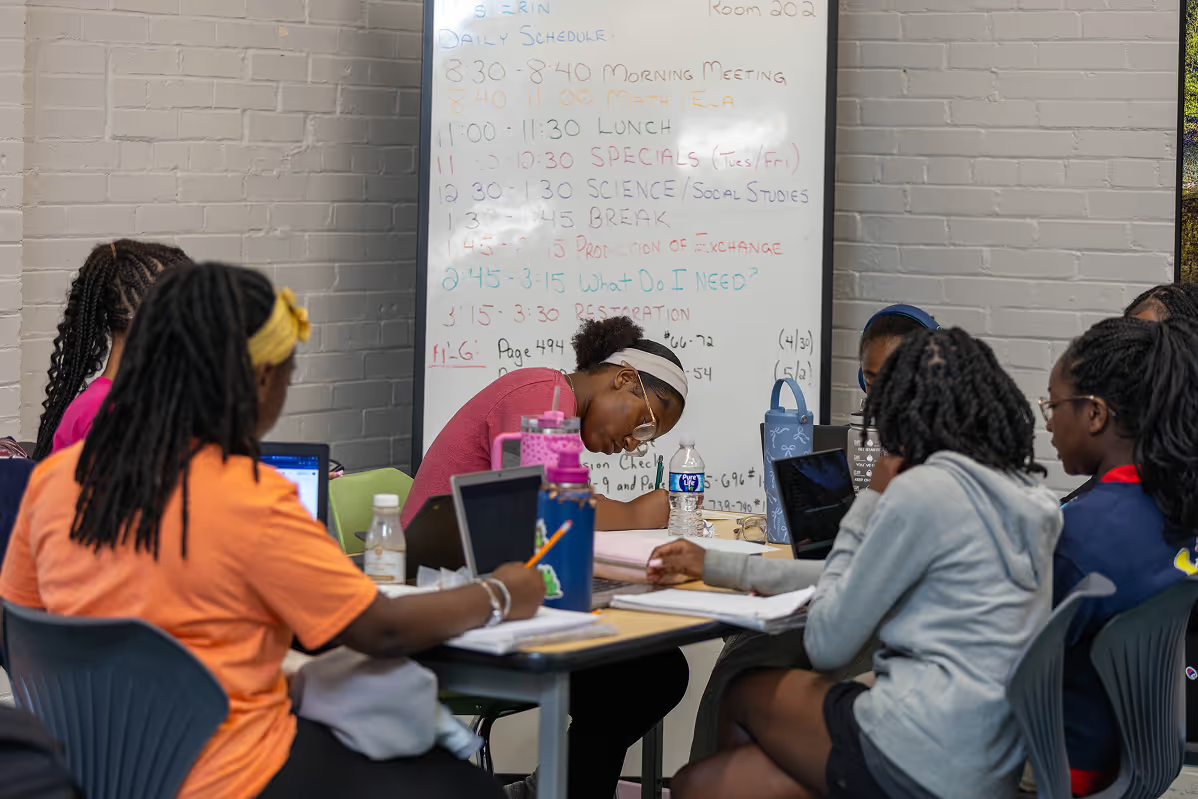

Today, City Garden serves 620 students in kindergarten through eighth grade and is housed in a new building on Folsom Ave. The school consistently ranks as one of the top-performing public charter elementary schools in St. Louis, and, in 2017, was awarded Missouri’s first 10-year public charter renewal for its strong student achievement results.

“No one is more motivated and determined to ensure our children have the best possible education.”

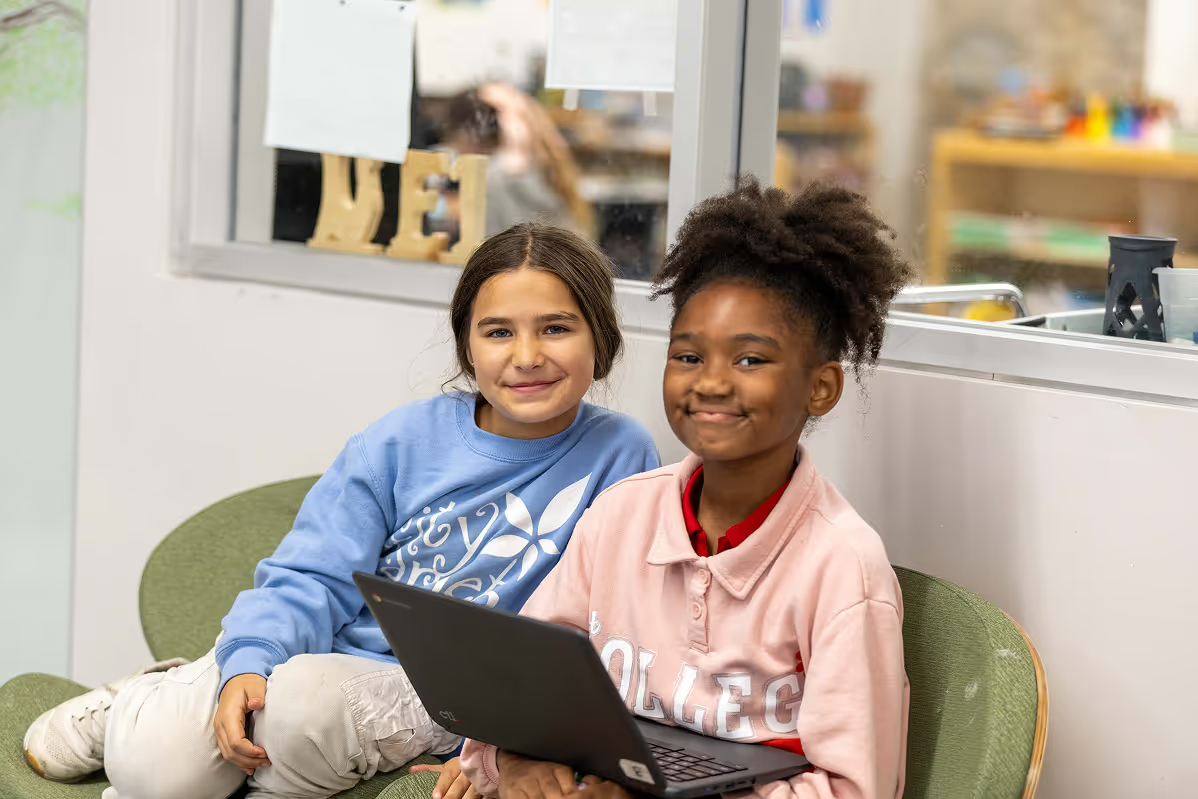

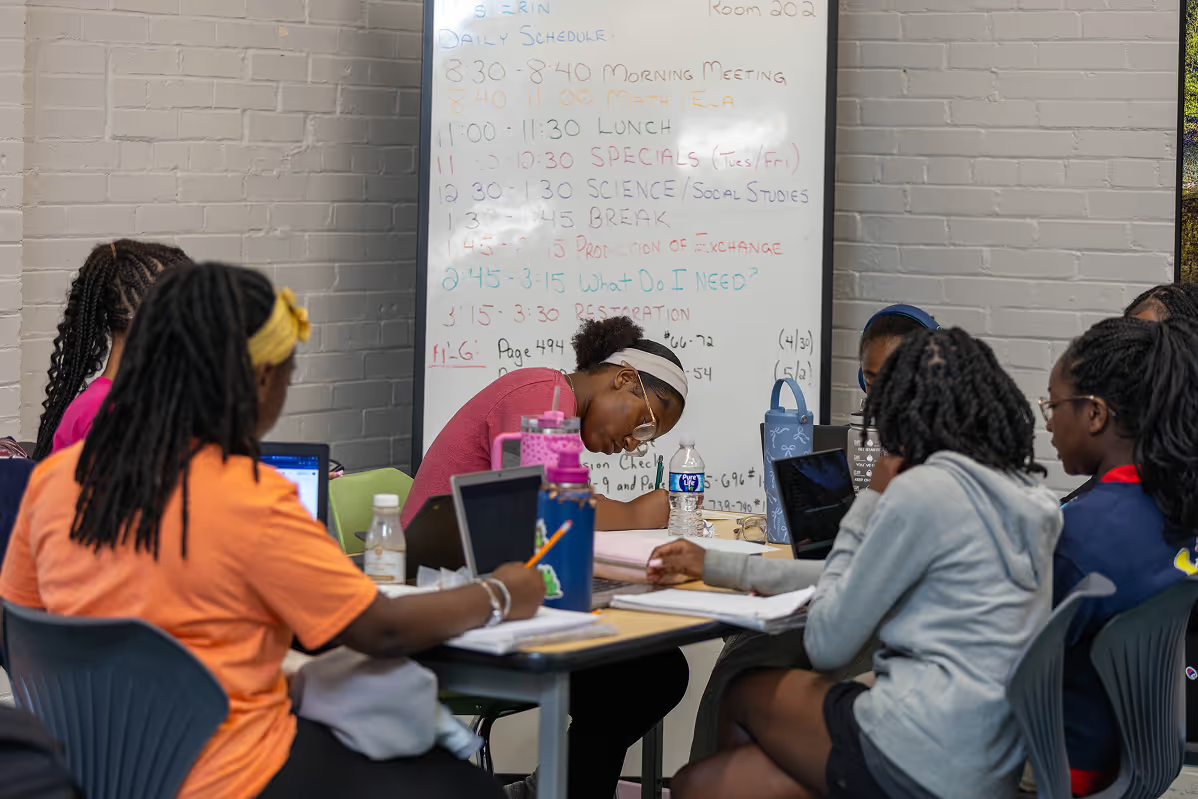

In keeping with the Montessori method, children are grouped in mixed-age classrooms and use specialized learning materials. Letter and percentage grades are not given until after sixth grade. Huck says public charter school flexibility gives City Garden the leeway to implement curriculum and instruction in ways traditional public schools cannot—and that’s the point.

“As public charter schools, the bar is high. We exist to do something different and be something different,” Huck says. “It’s really important to be clear about what you’re bringing to the ecosystem and bringing to the community you serve.”

However, as word has spread about City Garden’s success, the school’s desirability has attracted an influx of new families and development to the area, leading to some displacement of low-income families. To counter this unintended consequence, the school formed the Coalition for Neighborhood Diversity and Housing Justice and partnered with community development organizations, housing developers, and residents to successfully advocate for an increase in affordable housing in the surrounding neighborhoods. In 2018, City Garden joined with other public charter schools to help pass a bill that allows Missouri public charter schools to give enrollment preference to free and reduced lunch eligible students.

Huck says this steadfast fidelity to serving a diverse, integrated population stays strong because of City Garden families. “I love the fact that our school was founded by parents,” she says. “No one is more motivated and determined to ensure our children have the best possible education. We know what our children need, and we want that for our kids and all kids.”